(Rose and Joseph P. Kennedy, U.S. Ambassador to the Court of St. James’s, 1940)

Ambassador Joseph P. Kennedy’s shocking remarks before the Navy’s General Board in the fall of 1940 (see part 1 of this blog) raise a host of questions. What kind of man was Kennedy? Why did he have such a low opinion of the British and the competence of their government? Why did President Franklin D. Roosevelt appoint him as British ambassador and why didn’t FDR fire him? And how was it that such a man as Kennedy could have raised an admired son like John F. Kennedy, our 35th president. In this second part of my blog on Kennedy, I will attempt to shed some light on these questions based on his personal history, character, and public service.

An Irish Catholic born in 1888 into a political family in East Boston, MA, Joseph P. Kennedy was street-smart, supremely self-confident, hard-working, attractive, and a Democrat. As an Irish Catholic in Protestant Brahmin Boston, he was an outsider. Although he graduated from Harvard in 1912, the degree did not magically open doors for him, and he had to make his own path.

From his twenties onward, Kennedy was highly successful in business, and at a young age he amassed a substantial fortune in a variety of ventures, including banking, securities trading, the entertainment industry, real estate, and shipping. Kennedy’s success was entirely self-made. However, his business reputation was less than spotless, mostly because of shady securities trading practices. He engaged in market manipulation and trading on insider information at a time when those methods were not illegal. Although rumored to have bootlegged liquor during Prohibition, there is no support for such claims. Kennedy did legally import liquor after Prohibition’s end.

Kennedy married Rose Fitzgerald in 1914. The couple had 9 children, but Kennedy spent little time at home. He traveled extensively on business, and frequently vacationed separate from the family. He was always in the company of attractive women, and he had a notorious affair with actress Gloria Swanson. Despite his failings as a husband, he maintained a strong interest in his children.

In the presidential elections of 1932 and 1936, Kennedy supported Franklin D. Roosevelt. In recognition of Kennedy’s services in 1932, President Roosevelt awarded him two jobs in his first administration, 1st Chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission, newly formed to regulate the securities markets, and subsequently 1st Chairman of the Maritime Commission, an agency charged with stimulating U.S. merchant shipbuilding. Kennedy served briefly and successfully in both posts, although, as a man of large ego, he thought he should have been awarded a cabinet post.

Kennedy provided more significant support to FDR in 1936. He was valuable to the president because of his influence with Irish Catholic voters, not a natural constituency for FDR. On re-election to a second term, FDR felt obligated to give Kennedy a significant administration position. Kennedy wanted to be Secretary of the Treasury, a job held by a close friend of FDR. Alternatively, he wanted to be Ambassador to the United Kingdom, the most prestigious of U.S. diplomatic posts. Although FDR offered him Secretary of Commerce, a cabinet position that would have utilized his business expertise, Kennedy insisted on the ambassadorship, which he felt would bring prestige to his family. Roosevelt ultimately agreed.

Kennedy had the fortune to sustain the financial obligations of the ambassadorship, but he had no foreign policy or diplomatic experience. Indeed, he was known to be remarkably undiplomatic, typically blunt, and outspoken. Used to being in charge and throwing his weight around, Kennedy had little experience at being part of a team subordinate to the secretary of state and the president.

Kennedy arrived in Britain in February 1938, just as Hitler was threatening to invade Austria. Kennedy was an ardent isolationist, who believed that the U.S. should stay out of European disputes and wars so that American business could regain its footing after the Depression. Within two weeks of his arrival, Kennedy told the British the U.S. would not provide material or other support to them should they enter any conflicts; he tried to influence British internal politics by voicing support for the appeasement policies of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain over the opposition views of Winston Churchill; and he directly challenged the position of his boss, Secretary of State Cordell Hull, on U.S.-British relations. In relatively short order, Kennedy lost the confidence of Secretary Hull and President Roosevelt through intemperate, independent action. In his eagerness to avoid war, he even explored, without State Department authorization, the possibility of negotiations with persons close to Hitler. Increasingly, Hull and Roosevelt sidelined him by working around him and withholding information from him.

The British view of Kennedy was scarcely more positive than that of his superiors in Washington. Kennedy was welcomed in the social whirl of London and among those British who favored the appeasement of Hitler. However, Kennedy was convinced that the German war machine was invincible, and once war broke out, he became a defeatist. His attitude to towards the British soured, most likely because of his fear that the U.K. would draw the U.S. into war and that his children would be drafted to fight. He thought the British were too inept to avoid war. He impugned British motives in opposing Hitler, indicating their only concern was the survival of empire, not the preservation of democracy. He offended the British by his opposition to U.S. military and economic aid to them. During the blitz, he was scorned for decamping to the countryside while the British government and other ambassadors remained in London. British MP Josiah Wedgwood said of Kennedy:

We have a rich man, untrained in diplomacy, unlearned in history and politics, who is a great publicity seeker and who apparently is ambitious to be the first Catholic president of the U.S.

Kennedy returned to the United States in October 1940. No doubt concerned about Kennedy’s power to damage his bid for an unprecedented third term that November, FDR maintained cordial relations with Kennedy, even though FDR did not trust him or want him to continue as ambassador. In December, after FDR’s reelection, Kennedy resigned. Kennedy had essentially been frozen out of the responsibilities of ambassador because of his outspoken independence. His defeatism and dislike of the British had damaged his reputation, and because he could not be trusted to carry out someone else’s policy, he had destroyed any prospects for future public service.

Reading about Kennedy and his ambassadorship, I was repeatedly struck by parallels to Donald J. Trump and his presidency. MP Josiah Wedgwood’s description of Kennedy (quoted above) leaped off the page as equally descriptive of Trump. Both Kennedy and Trump grew up as outsiders, Kennedy as Irish in Brahmin Boston and Trump as a boy from Queens. In order to succeed, both were willing to engage in less-than-ethical business practices. At the time they sought public office, both were buoyed by wealth, felt entitled to power, and were motivated by outsized ego and ambition. Each wanted a prestigious job for which he was ill-prepared and temperamentally unsuited. Both were used to being in charge, and the independence that may have served each man in business did not play well in government. But while FDR was able maneuver Kennedy out of office, there is unfortunately no simple remedy for the destructive impact of Trump’s grand ambition to be president.

A final word about Kennedy and his role as a father. While Kennedy was rarely at the family home, he played an active role in his children’s upbringing. He followed their progress in school, was in touch with their teachers, and urged them to develop their skills and interests so that they could do something useful with their lives. He regularly wrote them warm letters of encouragement and used his many contacts to open doors to enriching and educational experiences for them. Thus, it is not surprising that Jack Kennedy developed into a balanced, well-grounded adult. And when Jack started to run for public office, Joe recognized that his controversial reputation might damage Jack’s chances so he remained strictly in the background. He provided financing and advice behind the scenes, but stayed out of the public eye.

Sources:

Nasaw, David, The Patriarch, The Remarkable Life and Turbulent Times of Joseph P. Kennedy, New York: The Penguin Press, 2012.

“Joseph P. Kennedy Sr.,” Wikipedia, last accessed 8.23.17, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_P._Kennedy_Sr.

(John Nance Garner and President Franklin D. Roosevelt meet on the presidential train in Uvalde, Texas in September 1942.)

(John Nance Garner and President Franklin D. Roosevelt meet on the presidential train in Uvalde, Texas in September 1942.) (At the upper right of this photo of bluejackets performing exercises on the aft deck of Iowa in July 1944, you can just see two OS2U floatplanes mounted on catapults the fantail. The crane used to retrieve the planes is folded between the catapults.)

(At the upper right of this photo of bluejackets performing exercises on the aft deck of Iowa in July 1944, you can just see two OS2U floatplanes mounted on catapults the fantail. The crane used to retrieve the planes is folded between the catapults.)

There was a soda fountain…

There was a soda fountain… And a bakery, although there was no case of goodies for customers to admire.

And a bakery, although there was no case of goodies for customers to admire. There was a barber shop, but the men didn’t have much choice in hair styles.

There was a barber shop, but the men didn’t have much choice in hair styles. The galley prepared meals, but the dining service wasn’t great. You had to wait…

The galley prepared meals, but the dining service wasn’t great. You had to wait… in a chow line and serve yourself.

in a chow line and serve yourself. For the treatment of medical problems, there was the “hospital” known as sick bay. Private rooms were unavailable. For the care of teeth…

For the treatment of medical problems, there was the “hospital” known as sick bay. Private rooms were unavailable. For the care of teeth… there was a dental office. Not too much privacy there either.

there was a dental office. Not too much privacy there either. The men did calisthenics on the quarterdeck…

The men did calisthenics on the quarterdeck… And there was plenty of deck swabbing to keep them fit.

And there was plenty of deck swabbing to keep them fit. (The wife of U.S. Vice President Henry A. Wallace, an Iowa resident, prepares to christen Iowa at the New York Navy Yard in Brooklyn, NY on August 27, 1942.)

(The wife of U.S. Vice President Henry A. Wallace, an Iowa resident, prepares to christen Iowa at the New York Navy Yard in Brooklyn, NY on August 27, 1942.) (Iowa slides down the launch way.)

(Iowa slides down the launch way.) (Tugs control Iowa after her hull enters the water.)

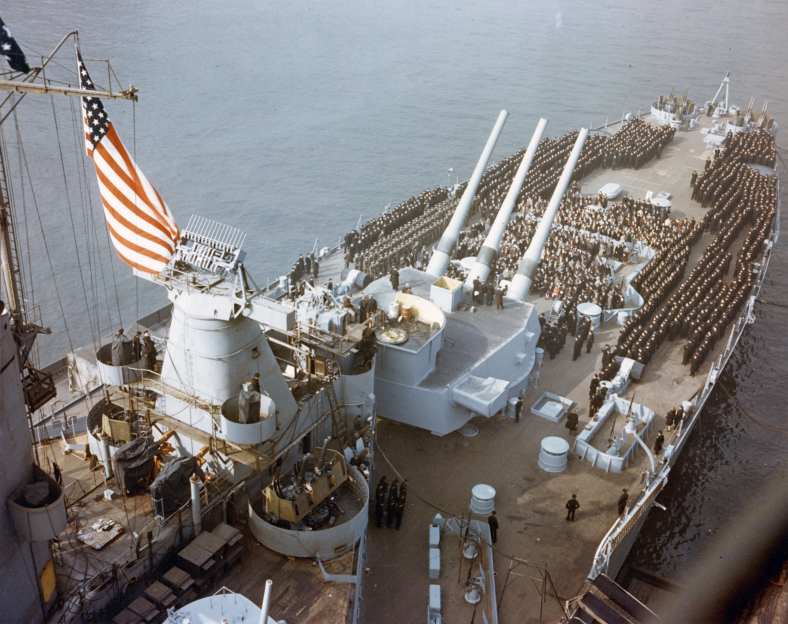

(Tugs control Iowa after her hull enters the water.) (Iowa is commissioned at the New York Navy Yard on February 22, 1943. The ceremonies took place on the ship’s quarterdeck under the 16″ guns of turret 3, the stern turret.)

(Iowa is commissioned at the New York Navy Yard on February 22, 1943. The ceremonies took place on the ship’s quarterdeck under the 16″ guns of turret 3, the stern turret.) (Iowa‘s bow displays the ship’s hull number “61”)

(Iowa‘s bow displays the ship’s hull number “61”) (A view of Iowa‘s superstructure.)

(A view of Iowa‘s superstructure.) (Iowa‘s bow viewed from the sky patrol post. The 16″ guns of turrets 1 and 2 are visible.)

(Iowa‘s bow viewed from the sky patrol post. The 16″ guns of turrets 1 and 2 are visible.) (A photo of an officer leading calisthenics on the quarterdeck while the ship’s band practices immediately below him. At the stern there are 2 OS2U float planes mounted on catapults that were used for observation purposes.)

(A photo of an officer leading calisthenics on the quarterdeck while the ship’s band practices immediately below him. At the stern there are 2 OS2U float planes mounted on catapults that were used for observation purposes.) (This photo taken from an aircraft carrier shows Iowa at Majuro in 1944. Majuro was a forward operating base where ships rested and re-provisioned between operations.)

(This photo taken from an aircraft carrier shows Iowa at Majuro in 1944. Majuro was a forward operating base where ships rested and re-provisioned between operations.) (USS Iowa’s anti-aircraft guns in the Pacific 1944)

(USS Iowa’s anti-aircraft guns in the Pacific 1944)